In early 1954 the Ryan Aeronautical Company was asked by the US Air Force to study the notion of a tail-sitting supersonic VTOL jet fighter. Drawing upon experience in designing the Model 38 and X-13 Vertijet, it proposed the Model 84 hook-suspended jet fighter, of which 14 different single- and twin-engine configurations were worked out. I was initially proposed to power the Model 84 with one Pratt & Whitney J75 turbojet, but Ryan later felt that two side-by-side General Electric J79 turbojets were essential to give the Model 84 a better combat radius. One Model 84 iteration, the Model 84F-7, had two 20,000 lb (89 kN) thrust General Electric X-301 afterburning turbofans, a top speed of Mach 2.5, and armament comprising 20 mm cannons and air-to-air missiles or one free-fall nuclear weapon. The Model 84 design resembled the Convair F-102 Delta Dagger and Dassault Mirage IIIA in having engine inlets on the sides of the forward fuselage, a delta wing, and a single vertical stabilizer. A hook would be fitted below the forward fuselage, and the pressurized cockpit was fitted with a swiveling ejector.

|

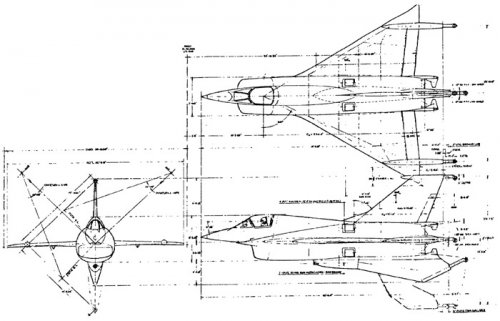

3-view drawing of the Ryan Model 115C tail-sitting supersonic VTOL jet fighter

|

In 1955 Ryan submitted the Model 84 design to the Wright Air Development Center, and after this proposal was well-received, it began work in 1955 on an improved supersonic VTOL tail-sitting fighter design, the Model 112, which had two General Electric J79s. The Model 112 design study continued into 1956, and Ryan offered two versions of the Model 112 to the US Navy, the Model 113 and Model 114. Meanwhile, the Air Force decided to continue funding Ryan's supersonic VTOL tail-sitter studies, and thus Ryan proposed the Model 115, which was similar to the Model 112 but had a longer fuselage to accommodate a larger bay housing a single tactical nuclear weapon or four air-to-air missiles. The final version, the Model 115C, envisaged in 1957, had a slightly stretched fuselage, greater operating range, circular inlets for the J79s, and greater range, and the airframe would be made from stainless steel. Alternative methods of boosting take-off performance were considered, including water injection and use of exotic fuels, and the Model 115C also was to used a tricycle landing gear. Despite promising lower operating costs, none of the Ryan designs for supersonic VTOL tail-sitter designs progressed to the hardware phase.

|

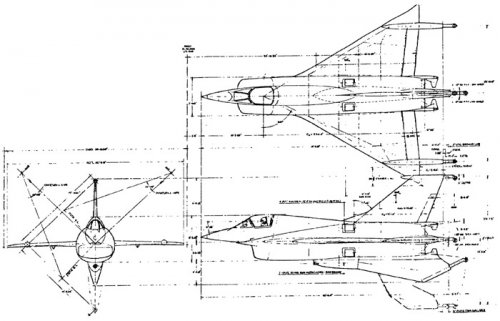

Top: Convair Configuration IVa

Bottom: North American design study for a supersonic tailsitter day fighter |

Even before testing of the Convair XFY, Convair investigated design studies for supersonic VTOL tail-sitting jet fighters, which like the turboprop-powered XFV hewed to the delta wing design philosophies for the F-102 Delta Dagger. Under a six-month USAF contract to study a lightweight supersonic tail-sitter issued in December 1953, Convair devised several proposals for supersonic VTOL tail-sitters, all of which shared a delta wing. One of the first supersonic VTOL tail-sitter design studies to emerge had a fuselage containing a jet engine fed by air flowing through a nose intake and unguided rockets carried in retracted forward-located packs. The aircraft stood on four dampened struts in wing nacelles and two vertical stabilizers, and the cockpit was housed in a large pod on the vertical stabilizer, with the pilot lying in a prone position. A revised design had the cockpit at the front of the aircraft, surrounded by the engine inlet. The Convair Configuration IVa had a fairly typical cockpit canopy design, an air inlet for the turbofan below the cockpit, and a ventral pod housing one M61 Vulcan 20 mm cannon and the landing strut. Wind tunnel tests of this design at NACA Langley in 1954 showed this proposal to be aerodynamically sound, but concerns about directional stability prompted Convair to devise a new Configuration IV design with delta-shaped canards on the nose and the ventral fin eliminated. North American is also known to have worked on a design for tail-sitting VTOL supersonic fighter, which stood upright on three vertical stabilizers and had three jet engines in the rear fuselage for vertical takeoff and four more in pairs in wingtip-mounted nacelles for forward flight, but this proposal is known only from drawings and no technical data is available at the moment.

|

Selected Lockheed CL-295 design studies, clockwise from top to bottom: CL-295-1, CL-295-3, CL-295-4, and CL-295-2. The CL-295-2 was also offered to the Navy as the CL-349-17.

|

In the meantime, Lockheed in 1954 investigated several designs for tail-sitting VTOL supersonic jet fighter under the company designation CL-295. The first two proposals, the CL-295-1 and CL-295-3, were based on the F-104 Starfighter and featured a retractable hook below the nose similar to that of the Ryan supersonic VTOL tail-sitters, as well as an exhaust flow control system, reaction jets, and a secondary stabilizing horizontal stabilizer for VTOL. The CL-295-1 was powered by one Wright TJC32C4 turbojet whereas the CL-295-3 used one General Electric X-84 turbofan and had a slightly shorter fuselage and wingspan in addition to being lighter, and both proposals would be armed with one 20 mm M61 Vulcan cannon and reach a speed of Mach 2. The next CL-295 design, the CL-295-4, was powered by two General Electric X-84 turbofans and stood on two vertical stabilizers and two wingtip nacelles when standing upright for VTOL, while featuring a canards on the nose. Successful test runs of the General Electric J79 turbojet prompted Lockheed to propose a J79-powered derivative of the CL-295-4 with twin dorsal vertical stabilizers, the CL-295-2. A version of the CL-295-2 was also offered to the US Navy as the CL-349-17 in response to the Navy's TS-140 specification for a VTOL jet fighter. The CL-295-68 was similar to the F-104 in having fuel tanks at the wingtips but had rear-mounted backswept wings, a cruciform tail empennage similar of that of the earlier XFV, and one Wright J67 turbojet with low-speed vane control in the exhaust flow, fed by air flowing through a ventral engine intake. The final design for the CL-295, the CL-295-77, had nose canards as in the CL-295-2/4 and CL-349-17 but had rear-mounted backswept wings with two General Electric X-84 turbofans at the wingtips. Armament for the CL-295-77 comprised Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, and the CL-295-77 used vanes in the exhaust flow and compressed air nozzles in the wingtips for low-speed vertical control, with normal control surfaces for horizontal flight.

By the late 1950s, the US Air Force and US Navy had come to the conclusion that the tail-sitter idea was conceptually a dead end when it came to operational practicality, and after hearing the new of flight tests of the Rolls-Royce Thrust-Measuring Rig (nicknamed the Flying Bedstead) realized that the best way for jet fighter to achieve vertical take-off and landing was to use swiveling jet engines, lift jets, and lift fans. In other word, by allowing a jet fighter to rise vertically above the ground through means of downward air, lift fans, swiveling jet engines, and separate jets could give the pilot visibility during the process of landing his/her plane vertically. Thanks to the British, the US armed forces and the aircraft industry in southern California could now look in this new approach to vertical take-off and landing for jet fighters.

References:

Bradley, R., 2013. Convair Advanced Designs II: Secret Fighters, Attack Aircraft, and Unique Concepts 1929-1973. Manchester, UK: Crécy Publishing.

Buttler, T., 2007. American Secret Projects: Fighters and Interceptors 1945 to 1978. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing.

Rose, B., 2013. Vertical Take-off Fighter Aircraft. Hersham, UK: Ian Allan Publishing.